Vue d'ensemble

CJPMO est fier de présenter les résultats d'un sondage pancanadien, coparrainé avec le Forum Musulman Canadien. Mené par une compagnie de sondage professionnelle, EKOS Research Associates, le sondage offre diverses optiques sur l'Islamophobie et le multiculturalisme au Canada.

CJPMO est fier de présenter les résultats d'un sondage pancanadien, coparrainé avec le Forum Musulman Canadien. Mené par une compagnie de sondage professionnelle, EKOS Research Associates, le sondage offre diverses optiques sur l'Islamophobie et le multiculturalisme au Canada.

Les résultats de l'enquête sont disponibles en format .pdf ici, ainsi qu'ils sont présentés dans son entièreté ci-dessous.

Le sondage a été fait par EKOS Research Associates entre le 24 Novembre et le 4 Décembre 2018, avec un échantillon aléatoire de 1 079 adultes canadiens âgés de 18 ans et plus. La marge d'erreur associée à l'échantillon est de plus ou moins 3,0 %, 19 fois sur 20.

Les données statistiques brutes fournies par EKOS peuvent être trouvées dans les liens suivants. Le premier document ci-dessous contient les données "résiduelles" (c'est-à-dire les résultats incluant les réponses "pas de réponse" et "ne sais pas"); le deuxième document contient les statistiques une fois les données "résiduelles" enlevées:

- EKOS Données du Sondage sur l'Islamophobie -Incluant les données "résiduelles"

- EKOS Données du Sondage sur l'Islamophobie -Excluant les données "résiduelles"

Notez que tous les graphiques présentés sur cette page sont du domaine public, sans aucune restriction de droits d'auteur. Également, veuillez prendre note que l'entièreté des documents se trouve en anglais seulement. Nous nous excusons de cet inconvénient.

Sommaire exécutif

Un récent sondage mené par les Associés de recherche EKOS confirme que la discrimination religieuse – en particulier l’islamophobie – constitue un défi permanent pour la société multiculturelle du Canada. Le sondage a permis d’enquêter sur la discrimination religieuse de différentes façons, et a confirmé à maintes reprises l’existence d’un courant sous-jacent d’islamophobie. Néanmoins, le sondage a également révélé que de nombreux Canadiens reconnaissent le problème de la discrimination religieuse et de l’islamophobie au Canada, y sont fermement opposés et s’attendent à ce que le gouvernement prenne des mesures pour y remédier.

Un récent sondage mené par les Associés de recherche EKOS confirme que la discrimination religieuse – en particulier l’islamophobie – constitue un défi permanent pour la société multiculturelle du Canada. Le sondage a permis d’enquêter sur la discrimination religieuse de différentes façons, et a confirmé à maintes reprises l’existence d’un courant sous-jacent d’islamophobie. Néanmoins, le sondage a également révélé que de nombreux Canadiens reconnaissent le problème de la discrimination religieuse et de l’islamophobie au Canada, y sont fermement opposés et s’attendent à ce que le gouvernement prenne des mesures pour y remédier.

Les Associés de recherché EKOS (https://www.ekos.com/) ont mené un sondage en ligne à l’échelle nationale auprès de 1079 Canadiens, entre le 28 novembre et le 4 décembre 2017, pour le compte du Forum Musulman (http://fmc-cmf.com) et des Canadiens pour la Justice et la Paix au Moyen-Orient (http://cjpme.org). L’enquête avait pour objectif : 1) Explorer les attitudes envers la discrimination religieuse, l’islamophobie et le multiculturalisme au Canada. 2) Essayer d’évaluer la gravité des problèmes. 3) Déterminer si le discours politique actuel sur ces sujets reflète fidèlement les opinions des Canadiens. La marge d’erreur associée avec l’échantillon et de plus ou moins 3.1 points de pourcentage, 19 fois sur 20.

L'enquête a confirmé que l'islamophobie et la discrimination religieuse sont généralement des problèmes préoccupants au Canada. Mais l'enquête a également révélé que les attitudes envers la discrimination religieuse sont extrêmement polarisées politiquement. Par exemple, environ 50% des partisans du Parti libéral, du NPD et du Parti vert considèrent que la discrimination religieuse envers les musulmans constitue un problème, alors que seulement 14% des partisans du Parti conservateur le pensent.

Les réponses à l'enquête indiquent clairement que :

- Les Canadiens sont moins à l'aise avec une figure d'autorité qui porte le voile, par rapport à tout autre type de tenue religieuse. Par exemple, les Canadiens sont plus de deux fois plus susceptibles d'être mal à l'aise avec un premier ministre qui porte le voile (44%), qu'avec un premier ministre qui porte une croix (21%) - et presque 1.5 fois plus mal à l'aise qu'avec un premier ministre qui porte une kippa (30%).

- Les Canadiens sont plus susceptibles d'avoir des stéréotypes négatifs sur les musulmans que sur les chrétiens ou les juifs. Par exemple, les Canadiens considèrent que les musulmans sont nettement moins tolérants, moins capables de s'adapter, moins ouverts d'esprit, plus violents et plus oppressifs envers les femmes que les chrétiens ou les juifs.

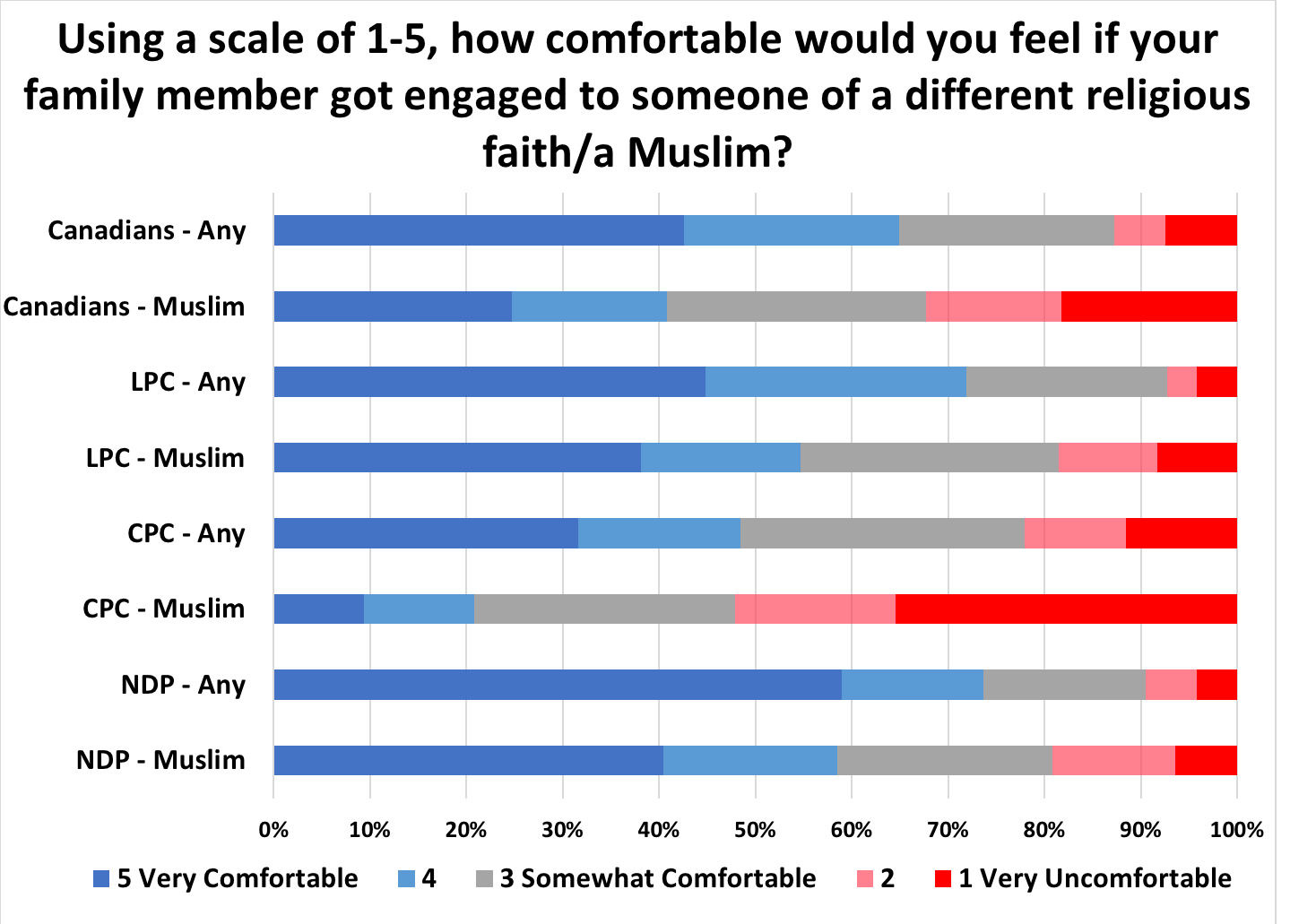

- Les Canadiens sont moins confortables avec l'idée d'accueillir un musulman dans leur famille qu'une personne d'une autre religion. Alors que seulement 12% des répondants ne sont pas confortables avec l'idée qu'un membre de leur famille se fiance avec une personne ayant des convictions religieuses différentes, 31% affirment être mal à l'aise avec l'idée qu'un membre de leur famille se fiance à une personne musulmane.

- Les Canadiens croient en la protection des droits religieux en général, mais sont moins préoccupés par les droits religieux des musulmans. Par exemple, 82% des répondants accordent de l'importance à la liberté religieuse en général, mais seulement 68% des Canadiens accordent de l'importance à la protection du droit des musulmans à pratiquer leur religion.

- Un nombre surprenant de personnes (17%) perçoivent la communauté musulmane canadienne comme un monolithe avec des points de vue uniformes. Seulement la moitié des Canadiens reconnaissent la diversité des points de vue inhérents à la communauté musulmane canadienne.

Pourtant, en même temps, les Canadiens sont très conscients du problème. Lorsqu'on leur demande directement si l'islamophobie existe au Canada, 81% des répondants ont répondu par l'affirmative, et 60% estiment que le gouvernement devrait prendre des mesures pour combattre l'islamophobie au Canada.

Les personnes interrogées ont également exprimé leur foi dans le modèle multiculturel canadien. Par exemple, lorsqu'on leur a demandé comment le Canada devrait répondre aux défis du multiculturalisme, la recommandation la plus populaire (48% des répondants) était simplement de mieux faire appliquer les lois existantes pour protéger les minorités contre la discrimination et les crimes haineux.

L'enquête a également montré clairement que de nombreux dirigeants politiques ratent la cible lorsqu'ils s'expriment au sujet de l'islamophobie. Alors que certains dirigeants politiques ont laissé entendre que la définition de l'islamophobie n'est pas claire, dans l'ensemble, 70% des Canadiens et près de 60% des partisans du Parti conservateur affirment savoir parfaitement ce que c'est. Comme mentionné précédemment, 81% des répondants au sondage confirment qu'ils croient que l'islamophobie existe au Canada.

Dans l'ensemble, 57% des répondants à l'enquête considèrent que l'islamophobie est un problème de plus en plus préoccupant au Canada, et ce nombre augmente à 70% lorsqu'on ne s'intéresse qu'aux partisans du Parti libéral, du NPD et du Parti vert. Cependant, les partisans du Parti conservateur, et les Québécois dans leur ensemble ont manifestement des opinions très différentes sur l'islamophobie comparativement aux autres segments de la population.

Les dirigeants politiques doivent comprendre que les inquiétudes au sujet de l'islamophobie ne feront qu'augmenter avec le temps, car les électeurs de la génération du millénaire sont toujours moins susceptibles d'adopter des attitudes islamophobes que les électeurs plus âgés. Par exemple. 54% des Canadiens qui ont moins de 35 ans sont confortables avec l'idée d'une première ministre portant le voile, alors que seulement 31% des Canadiens de plus de 55 ans le sont. Et les jeunes Canadiens (35 ans et moins) sont deux fois moins susceptibles d'être inconfortables à l'idée qu'un membre de leur famille se fiance avec une personne musulmane que la moyenne.

Alors que l'enquête actuelle confirme et élargit la compréhension du problème de l'islamophobie identifié dans des enquêtes précédentes, les nouvelles découvertes donnent également au gouvernement plus de raisons de s'attaquer aux attitudes islamophobes. Le sondage montre clairement que les Canadiens chérissent leurs traditions multiculturelles et que le gouvernement doit travailler plus fort pour que le multiculturalisme fonctionne, pour les musulmans ainsi que pour toutes les autres communautés de la mosaïque Canadienne.

Survey Introduction

Understanding Islamophobia

The term “Islamophobia” was first coined in 1997 as an “unfounded hostility towards Muslims, and therefore fear or dislike of all or most Muslims.”[1] The Merriam-Webster dictionary currently defines Islamophobia as the “irrational fear of, aversion to, or discrimination against Islam or people who practice Islam.” The Oxford English dictionary defines Islamophobia as “dislike of or prejudice against Islam or Muslims, especially as a political force.”

“Islamophobia consists of violence against Muslims in the form of physical assaults, verbal abuse, and the vandalizing of property, especially of Islamic institutions including mosques, Islamic schools and Muslim cemeteries. Islamophobia also includes discrimination in employment — where Muslims are faced with unequal opportunities — discrimination in the provision of health services, exclusion from managerial positions and jobs of high responsibility; and exclusion from political and governmental posts. Ultimately, Islamophobia also comprises prejudice in the media, literature, and everyday conversation”[2]

Many scholars believe that Islamophobia threatens not only Muslims, but also anyone who is simply perceived as Muslim. At a political rally in 2017, for example, NDP leader Jagmeet Singh – not a Muslim, but a visible Sikh – was repeatedly and falsely accused by a heckler of advocating Sharia law. [3] As this and other examples demonstrate, Islamophobia can impact even non-Muslims because of their dress, race, name, language, accent, or other cultural markers.[4] [5]

Contextualizing Canadian Islamophobia

Islamophobia seems to be on the increase in many Western societies, including Canada. In a 2013 Angus Reid poll, 54 percent of Canadians held an unfavourable view of Islam with the number increasing to 69 percent among Quebec residents.[6] In a 2015 report by the CJPME Foundation, researchers highlighted a trend of Canadian government-sanctioned Islamophobia. This type of Islamophobia is particularly troubling as it can imperil rights to citizenship, access to employment, and community integration.[7]

While government-sanctioned Islamophobia is particularly egregious, most manifestations of Islamophobia are much subtler and manifest themselves in day-to-day acts of petty racism. Although Canadian law prohibits employers from discriminating on the basis of religious affiliation or race, unemployment rates are significantly higher amongst Muslim Canadians than among other groups with similar skills.[8] Moreover, a 2012 study by the Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse du Quebec found that job candidates with traditionally Quebecois or Canadian names were 1.63 times more likely to receive a call back than candidates with similar skills who had traditionally Arab names.[9]

Another example is that of Herouxville, Quebec where civic leaders implemented a code of conduct in 2007 for new immigrants, despite being home to virtually zero foreign-born individuals or visible minorities. The bizarre document was clearly aimed at Muslim Canadians as it forbade the wearing of head coverings, and certain archaic practices sometimes associated with Islamic stereotypes.[10]

While Islamophobic sentiment appears to be more common in Quebec, mosques in cities such as Vancouver, Edmonton, Toronto, Ottawa and Hamilton have also been vandalized in recent years.

Many Muslims living in the West experienced a rise in Islamophobic sentiment following the events of September 11th, 2001.[11] Multiple scholars have attributed the more recent increase in Islamophobia in the West to the perceived connection between Muslim individuals and global violence or terrorism.[12] Violent acts perpetrated by self-identified Islamic groups around the world have appeared more frequently in news media in recent years. The rise of the Islamic State group (often referred to as ISIS or ISIL) and the media coverage they have received likely contributes to negative stereotypes associated with Islam. The same can be said of groups such as Al-Shabaab, Boko Haram and the Taliban, and acts of terror committed by Muslim extremists in Europe and elsewhere. While loathing of the terrorist acts committed by such groups is understandable, it is patently unfair to penalize innocent Muslim-Canadians for the acts of such groups. In fact, key Muslim leaders in Canada and other Western countries consistently condemn the acts of such groups overseas.[13]

Motion M-103 and the Quebec Mosque Attack

Noticing the increase in Islamophobia incidents in Quebec, the Canadian Muslim Forum worked with Liberal MP Frank Baylis to launch an anti-Islamophobia parliamentary ePetition (e-411) in June 2016.[14] By the time Petition e-411 closed four month later, it had received almost seventy thousand signatures – the highest number of signatures on any single petition to date.

Inspired by the groundswell of support for the petition, outgoing NDP Leader Thomas Muclair secured unanimous consent in October, 2016 for a Parliamentary motion based on the wording of the e-411.[15] On that occasion, every MP present in the Commons chamber agreed to a motion “condemning all forms of Islamophobia.”[16]

Three months later, on January 29th, 2017, six Muslim men were brutally killed and 19 injured by a right-wing attacker at a Quebec City mosque.[17] This attack focused attention on the alarming presence of Islamophobia in Canada, and the deadly consequences of this racism. Shortly after the mosque attack, in February, Liberal MP Iqra Khalid introduced parliamentary motion M-103, a private member’s motion which called for Parliament to “condemn Islamophobia and all forms of systemic racism and religious discrimination.” It also recommended a study of systemic racism and religious discrimination by the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage.[18] Unlike Mulcair’s motion, M-103 immediately received significant backlash from the right-leaning voices across Canada and intensified a nationwide debate on Islamophobia.

When motion M-103 was tabled, the Conservative leadership race was in full swing. With this platform, Conservative leadership candidates debated the question repeatedly, with some questioning the very existence of Islamophobia. While many Canadians understood the timeliness of M-103, certain elements of Canadian society questioned the intents of M-103, arguing against the need to highlight “Islamophobia” among other forms of religious discrimination. [19] [20] During the height of the debate around M-103, Khalid reported that she received thousands of hate messages, racist slurs, and death threats for her role in sponsoring M-103.[21]

While M-103 ultimately passed in the House of Commons in March 2017 by a vote of 201-91, the behaviour of some politicians was perplexing. During the M-103 debate, politicians who had supported the October 2016 motion now claimed to be unsure of what Islamophobia actually was. Other political voices went on to suggest that this M-103 would limit their free speech – putting a chill on criticism of certain Muslim practices. Still other politicians suggested that there was an attempt to give Islamophobia preferential treatment by identifying it by name in Motion M-103.[22] [23]

By citing Islamophobia when speaking against religious discrimination or systemic racism, Khalid and others call attention to the fact that it is especially Muslims who are experiencing religious discrimination and systemic racism in Canada today. There is no indication that the safety, rights and opportunities of Christians in Canada are in jeopardy in 2017; whereas this is not true for Canadian Muslims.

The conversation around Islamophobia in Canada is far from over. Canadians are anxious to see the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage’s M-103 report and recommendations. The Committee was charged to “develop a whole-of-government approach to reducing or eliminating systemic racism and religious discrimination including Islamophobia, in Canada” and tasked to “collect data to contextualize hate crime reports and to conduct needs assessments for impacted communities.”[24] While the committee is expected the address the problem of religious discrimination in general, there is clearly a need to recognize and address the special challenges facing Muslims in Canada today.

Other Canadian Surveys on Islamophobia

Other surveys of Canadians over the past several years show consistent and growing evidence of Islamophobia and religious discrimination. A more detailed summary and links to these studies is provided in Appendix 1.

Survey Methodology

This study reports Canadian respondents’ replies to the following eight areas of questioning: [25]

- What is the best way for the government to respond to the challenges that come with multi-culturalism today?

- How do you feel when figures of authority in Canada wear different religious garb?

- How much of a problem do you believe religious discrimination (and religious discrimination against Muslims) is in Canada?

- How accurately do certain words and phrases describe different religious groups in Canada?

- How comfortable would you feel if a member of your family became engaged to someone of a different religious faith (or to a Muslim)?

- How important do you believe it is that the government protect the rights of all Canadians (and Muslim Canadians) to practice their religion?

- How varied do you believe the views of Canadian Muslims are?

- To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements?

- The definition of Islamophobia is not clear to me

- Islamophobia does not exist in Canada

- Islamophobia is an increasingly disturbing problem in Canada

- The government must take action to combat Islamophobia in Canada

- The concept of Islamophobia is having the effect of limiting free speech in Canada

EKOS Research Associates (EKOS), an experienced public opinion research firm, was hired to conduct an on-line poll to seek answers to these questions. EKOS is a full-service consulting practice, founded in 1980, which has evolved to become one of the leading suppliers of evaluation and public opinion research for the Canadian government. EKOS specializes in market research, public opinion research, strategic communications advice, program evaluation and performance measurement, and human resources and organizational research.

Between November 24 and December 4, 2017, a random sample of 1,079 Canadian adults from EKOS’ online panel, Probit, aged 18 and over, completed the survey. The survey was made available to all respondents in either English or French. The margin of error associated with the sample is plus or minus 3.0 percentage points, 19 times out of 20. The margin of error increases when the results are sub-divided.

EKOS statistically weighted all the data by age, gender, education and region to ensure the sample’s composition reflects that of the actual population of Canada, based on 2016 census data. EKOS weighted the data based on the 2011 Census, for age, gender, region, and education.

The full data, both with residuals (“don’t know” and “no response” percentages included) and without residuals can be found at http://cjpme.org/islamophobia.

In most cases, no more than 10% of respondents did not reply or checked “don’t know,” and in most cases, far fewer than 10% did so. As such, these responses do not substantially affect the overall results. However, in sub-sets of some variables, a larger proportion of respondents did not express an opinion (by checking “don’t know/no response”). In general, these appeared to reflect their lack of information and/or lack of interest in the topic, because they tended to occur among those with limited education.

Survey Results

1. Canadians strongly support the values implicit in Canadian multiculturalism

This question asked respondents their opinion on how the government should address current challenges to Canada’s multiculturalism. It’s important to note that the response options were not mutually exclusive: a respondent could check any items that they felt applied. The survey question read:

“In your opinion, what is the best way for the government to respond to the challenges that come with multi-culturalism today?” The response options were:

- Better enforce existing laws to protect minorities from discrimination and hate crimes

- Provide cultural sensitivity training to government employees who deal with the public (e.g. police, judges, teachers, etc.)

- Screen new immigrants with a “Canadian values” test

- Pass new “values” legislation promoting common cultural practices

- Provide funds to historically disadvantaged communities

- Do nothing: Canada’s existing laws and Charter of Rights and Freedoms are sufficient

- Pass new laws to protect society against the influences of immigrants

Chart 1: In your opinion, what is the best way for the government to respond to the challenges that come with multi-culturalism today?

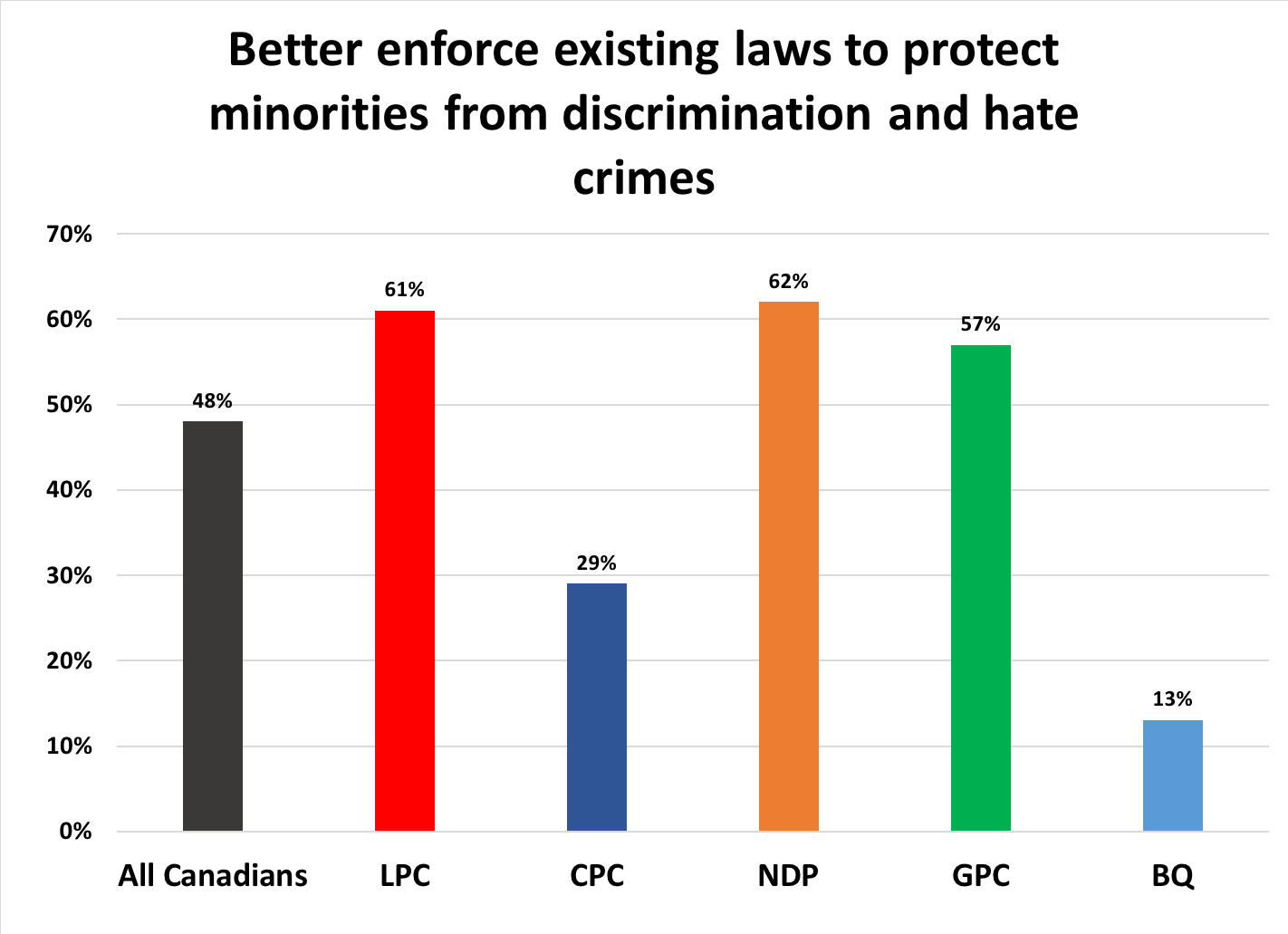

Chart 2: By political affiliation: Better enforce existing laws to protect minorities from discrimination and hate crimes

Multiculturalism has been a core component of Canada’s policy since the 1970s. While the United States adopted an assimilationist “melting pot” model for its multicultural society, Canada has promoted a “mosaic” model of multiculturalism that promotes cultural diversity across Canadian society. Canadian multiculturalism does not force immigrants to choose between their cultural heritage and participation in Canadian society. Given this history of Canadian multiculturalism, it is not surprising that the Prime Minister frequently repeats renditions of the following phrase: “Canadians understand that diversity is our strength. We know that Canada has succeeded—culturally, politically, economically—because of our diversity, not in spite of it.”[26]

In this question, the survey sought to gage current Canadian attitudes in light of recent attacks on multiculturalism from across the country. For example, the Parti Quebecois’ Charter of Values, Former Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s fear-mongering Islam-related rhetoric, and the xenophobic Conservative leadership campaign led by MP Kellie Leitch are each examples of campaigns attacking certain core tenets of multiculturalism.

Our survey results indicate that, whereas some Canadians have been spooked by this Conservative rhetoric, they are far from giving up on multiculturalism. In fact, Canadians are clearly concerned about threats to multiculturalism, and expect their government to protect the diversity Canadian society enjoys. And while none of the proposed options received a majority of responses, the top two choices – receiving 48% and 41% support respectively – were clearly options bolstering Canadian multiculturalism.

The most highly chosen course of action on this question, “[Canada must] better enforce existing laws to protect minorities from discrimination and hate crimes,” was supported by 48 percent of respondents, and indicates clearly that Canadians continue to have faith in the existing mechanisms supporting multiculturalism.

The second most recommended course of action also emphasizes Canadians’ interest in preserving and protecting our multicultural society. 41 percent of Canadians feel the government should “provide sensitivity training to government employees who deal with the public […]” Thus, far from putting the onus of successful multiculturalism on new arrivals, many Canadians believe that the government and its representatives need to adapt to a changing societal mosaic. A fifth of Canadians even believe that there should be some form of government funding made available to historically disadvantaged communities.

While the top two responses to this question suggest a deep and ongoing commitment to multiculturalism among Canadians, the third most popular response does reflect some of the angst expressed by some Conservative politicians. Fully 37 percent of Canadians feel that new arrivals should be subjected to some type of “Canadian Values” test. It’s important to note that this cultural anxiety is felt across all political parties. On the other hand, this percentage is much lower than the March 2017 CROP poll results, where 74 percent of respondents indicated they were in favour of a “Canadian values” test.

This apparent angst was also expressed in another response, where 17 percent of respondents suggested that “pass[ing] new laws to protect society against the influences of immigrants” was necessary. In addition, 22 percent of respondents felt it might be necessary to “pass new ‘values’ legislation promoting common cultural practices in Canada.” Indeed, these results confirm other recent survey data that suggest that some Canadians think minorities should do more to “fit in.”

Among these responses, political ideology plays a role in determining Canadian comfort levels with multiculturalism, as self-identified Conservative and BQ supporters ranked considerably higher in their desire to have a “Canadian values” test. Likewise, neither group prioritized the options that sought to better protect and support minority Canadians.

It is also important to point out the significant regional differences in the percentage distributions, as Quebecers seem to experience a similar angst described by Conservative politicians. From the very beginning, Quebec has expressed some hesitancy, even resistance, to the policy of multiculturalism. Certain strands of Quebec nationalism view the policy of multiculturalism as a political ploy to weaken the status of Quebec as a distinct society. Quite opposite to Quebec, residents of Atlantic Canada were particularly concerned about protecting minority populations and preserving the multicultural character of Canada.

2. In terms of common religious garb, Canadians are least comfortable with the hijab

In this question, survey respondents were asked to rate their comfort level with four types of religious garb – a cross, a kippah, a hijab, and a turban – on a scale of 1 to 5, from very comfortable to very uncomfortable. The question in the survey polled respondents about religious garb as worn by 1) the prime minister, 2) a supervisor at work, and 3) a police officer.

Distinctive headgear and other forms of dress are a feature of several religions. For example, some men of the Sikh faith wear a turban, some Jewish men wear a kippah or yarmulke (a cap) while some Muslim women wear a hijab (headscarf), and some Christians wear crosses around their necks.

Using a scale of 1 to 5, how comfortable would you feel if your [Prime Minister]/[Supervisor at work]/[police officer] wore a:

- Turban

- Kippah (Yarmulke)

- Hijab

- Cross

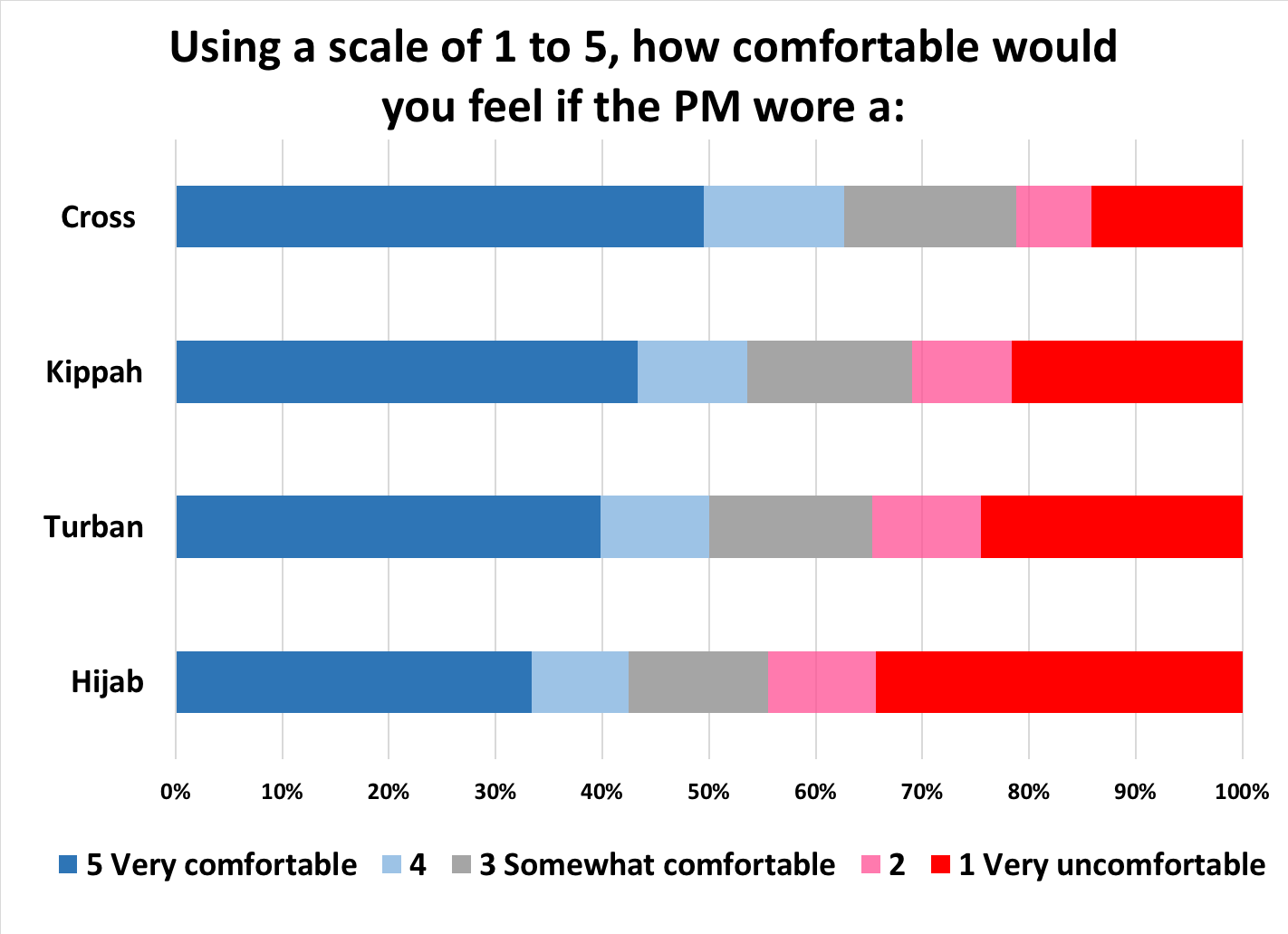

Chart 3: How comfortable would you feel if the prime minister wore a cross/kippah/turban/hijab?

Chart 4: How comfortable would you feel if a police officer who has pulled you over wore a cross/kippah/turban/hijab?

As a diverse and multicultural society, Canada has often debated the impact of religious symbols and dress in the public sphere. Quite often, the debate centers around the extent to which the practices of religiously observant Canadians may influence public life and the provision of government services. While the majority of Canadians are generally accepting of diverse religious dress and symbols, recent incidents suggest there are some religious symbols that are more accepted than others. For example, in 2016 a Quebec Muslim woman was asked to remove her hijab during a hearing in traffic court,[27] and in 2017, the Quebec government passed a bill banning face veils for people receiving government services. [28]

Without seeking to pit various forms of religious dress against each other, this question sought to determine Canadians’ level of comfort with visible markers of religion, such as dress and headgear as worn by figures of authority. While symbolically, there is little difference between the turban, kippah, cross and hijab – i.e. each is a symbol of one’s devotion to one’s religious beliefs – the survey indicated quite differing public attitudes on each.

First, with all three figures of authority (prime minister, police officer, supervisor at work), Canadians were consistently least comfortable with the hijab as compared to other religious garb. In reference to the prime minister, only 21 percent of respondents expressed discomfort with the cross, 30 percent expressed discomfort with the kippah, 34 percent expressed discomfort with the turban, while fully 44 percent of respondents expressed discomfort with the hijab. Likewise, when asked about comfort levels vis-à-vis a new supervisor in religious garb, 11 percent of respondents expressed discomfort with the cross, 19 percent expressed discomfort with the kippah, 21 percent expressed discomfort with the turban, while fully 30 percent of respondents expressed discomfort with the hijab.

This relative discomfort with the hijab could relate to negative reports or perceptions of Muslims internationally as propagated in news reports and related media. Populist politicians, in turn, exacerbate these negative perceptions by pushing divisive political agendas. For example, in the 2015 elections, former Prime Minister Stephen Harper put great emphasis on his move to ban women who wear niqabs from taking the Canadian citizenship oath.[29] Likewise, in late 2017, the Quebec provincial government introduced Bill 62, which sought to restrict Muslim women from wearing the niqab when receiving government services.[30] By comparison, in recent decades, no political party or politician targeted Christians, Jews or Sikhs because of their religious garb.

Second, the survey revealed that Canadians were highly sensitive about the religious garb worn by the country’s prime minister. For example, while 30 percent of Canadians would be uncomfortable with a supervisor who wears a hijab, and 39 percent of Canadians would be uncomfortable with a police officer who wears a hijab, fully 44 percent of Canadians would be uncomfortable with a prime minister who wears a hijab. These disparities may stem from the fact the Prime Minister is often portrayed as the archetypal “Canadian,” or ambassador who represents the country. This interpretation would infer that Canadians are less comfortable with a visibly Muslim woman representing Canada on the domestic or international stage; or that many Canadians have not accepted Islam as being an integral part of Canada’s society.

As with many of the questions in the survey, both Quebec respondents, and respondents who identify as Conservative party supporters tend to be much less comfortable with a prime minister in a hijab than other groups. While the majority of Canadians across party lines are at least somewhat comfortable with a prime minister in hijab, only 33 percent of Conservative respondents and 23 percent of BQ respondents share this comfort. This may be explained by Quebec’s tradition of secularism in recent decades, and by the fact that several Conservative figures in Canada have sought to position Muslim dress as something uncivilized.[31] Likewise, the majority of respondents who identified as Quebeckers or Conservatives were also the least comfortable with being pulled over by a police officer wearing a hijab, or having a supervisor who wears a hijab.

In each variation on the question, age is an important factor associated with the comfort level of Canadians vis-à-vis various religious symbols. While the majority of Canadians under age 35 are quite comfortable with each of the religious garb mentioned (turban, cross, kippah and hijab), those who are over 55 have a tendency to be much less comfortable with these symbols. For instance, 54 percent of Canadians under age 35 are quite comfortable with a prime minister who wears a hijab, whereas only 34 percent of Canadians over 65 are comfortable with a prime minister who wears a hijab. It is noteworthy to point out that these results among older Canadians do not stem from feelings of generalized discomfort with religion in the public sphere. In fact, with the exception of Quebec respondents, 61 percent baby boomers are quite comfortable with the notion of a Canadian Prime Minister or police officer with a cross. Yet the very same respondents are markedly uncomfortable with the other specific forms of religious dress.

Level of education was also an important factor in predicting the comfort level of Canadians vis-à-vis various religious symbols – greater comfort with religious garb strongly correlated with higher levels of education. For example, only 36 percent of respondents with a high school education are comfortable with a prime minister who wears a hijab while 55 percent of Canadians with a post-graduate degree are comfortable with a prime minister who wears a hijab.

It should be noted that the hijab is the only religious symbol listed that is exclusively worn by women. To this point, sexism could also have factored into the overall results, increasing the percentage of those who are uncomfortable with a figure of authority wearing a hijab.

Chart 5: How comfortable would you feel if the prime minister wore a turban?

Another interesting result from this survey question was Canadians’ attitude toward a prime minister who wore a turban. This question is of particular political significance given the recent nomination of Jagmeet Singh – a turban-wearing Sikh – to the leadership of the federal NDP. The survey indicates that nearly 50% of Canadians would be comfortable with a prime minister in a turban. This is more than those who are comfortable with a prime minister in a hijab, but less than those who are comfortable with a prime minister in a kippah or wearing a cross.

By political party preference, the results regarding a prime minister in a turban are even more interesting. 57 percent of Liberal supporters, and 63 percent of both NDP and Green supporters are comfortable with a turban on a prime minister. While these numbers overall come across as an affirmation of Canada’s multicultural nature, one cannot ignore the fact that 23 percent of the supporters within Mr. Singh’s own party are not comfortable with a prime minister in a turban. Comfort with a turban on the prime minister drops even more among Conservative (33 percent) and Quebec supporters (24 percent.)

3. Views on religious discrimination against Muslims are highly politically polarized

This question took a split sample approach where respondents were randomly asked one of two related questions:

- On a scale of 1 to 5, how much of a problem do you believe religious discrimination is in Canada?

- On a scale of 1 to 5, how much of a problem do you believe religious discrimination against Muslims is in Canada?

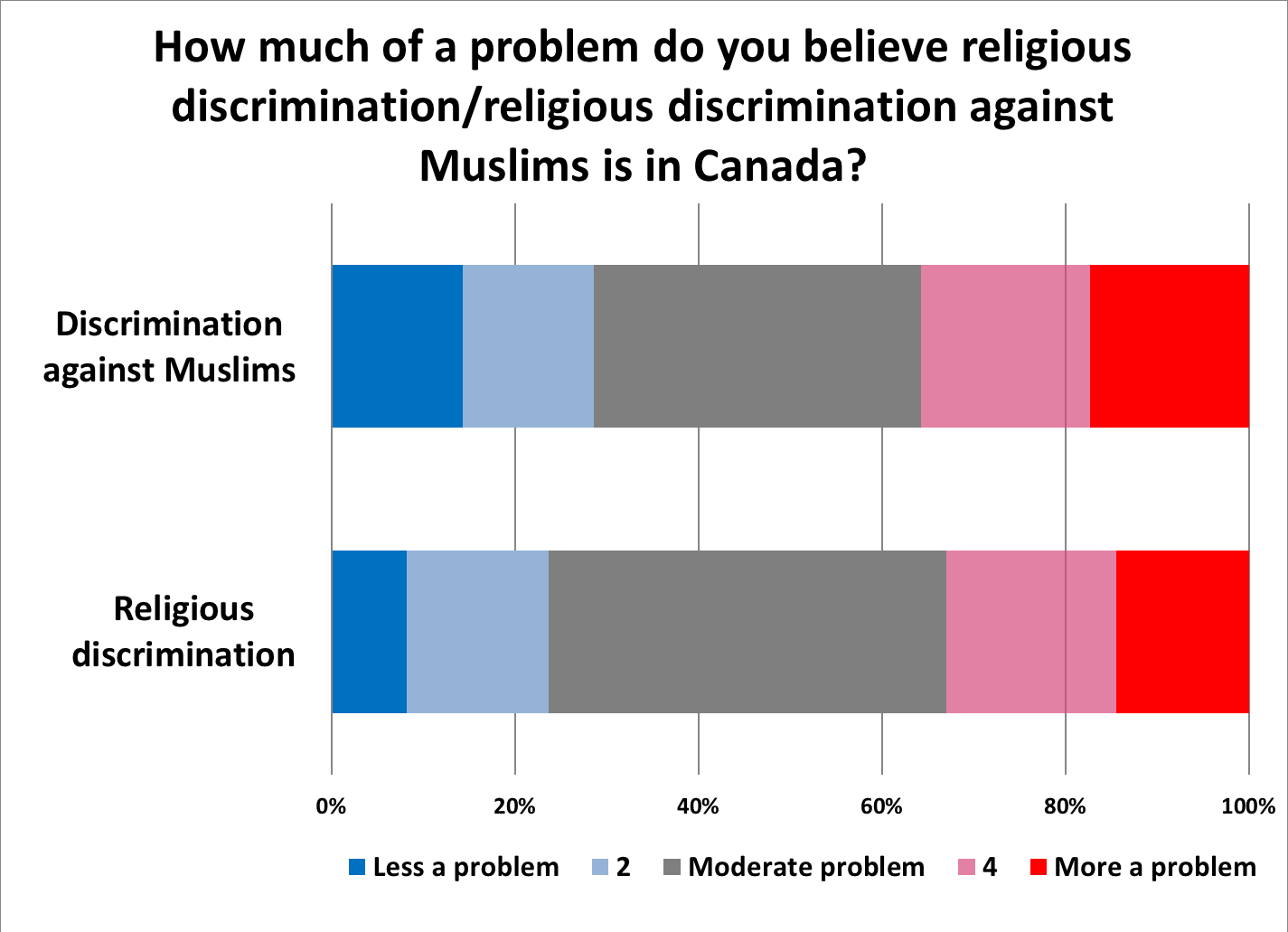

Chart 6: How much of a problem do you believe religious discrimination (against Muslims) is in Canada?

Chart 6B: How much of a problem do you believe religious discrimination (against Muslims) is in Canada?

In this question, about a third of respondents indicated that they felt religious discrimination overall is a large problem in Canada. A similar number felt the same way about religious discrimination against Muslims, specifically. However, the real story behind the results lies in the political polarization evident in the response:

- When asked about religious discrimination in general, respondents who self-identified as Liberal, NDP and Green supporters fell largely in the middle, many considering it only a “moderate problem.” However, when asked about religious discrimination against Muslims, there was a far greater perception among these respondents that it was a more significant problem: 47% of Liberals, 49% of NDP, and 52% of Greens, vs. an average of 35% overall.

- However, respondents who self-identified as Conservative supporters tended to downplay the issue of religious discrimination. Only 24% felt religious discrimination generally is a problem, and even fewer (14%) of these respondents feel religious discrimination against Muslims specifically is a problem.

While opinions may vary, the survey response of Conservative respondents runs counter to the statistics regarding religious discrimination and hate crimes in Canada. Hate crimes against Muslims rose dramatically in 2015 and by 2016 represented one-third of all hate crimes in Canada. In addition, in 2016 the number of hate crimes targeting Arabs, West Asians and South Asians increased.[32] To explain this newest trend, experts suggest that “Muslims have become racialized in the West to the extent that ‘Muslim’ is conflated with brown/Arab/Middle-Eastern.”[33] Those who are thought to be Arab or South Asian are also assumed to be Muslim, and are thus targeted based on that assumption.

4. Muslims are viewed more pejoratively than other religious groups in Canada

This question was a split sample, whereby respondents were asked to rate their impressions of one of three different religious groups in Canada: Christians, Jews and Muslims. For each group, respondents were given 12 different words and phrases, and asked their opinion on how well each word or phrase described that group. The question was as follows:

Using a scale of 1 to 5 where 1 means does not describe at all and 5 means describes completely, please rate how well the following words or phrases best describes your impression of [Muslims]/[Jews]/[Christians] in Canada?

The words/phrases were:

|

|

Chart 7: How much do tolerant/adaptable/open-minded describe your impression of Muslims/Christians/Jews in Canada?

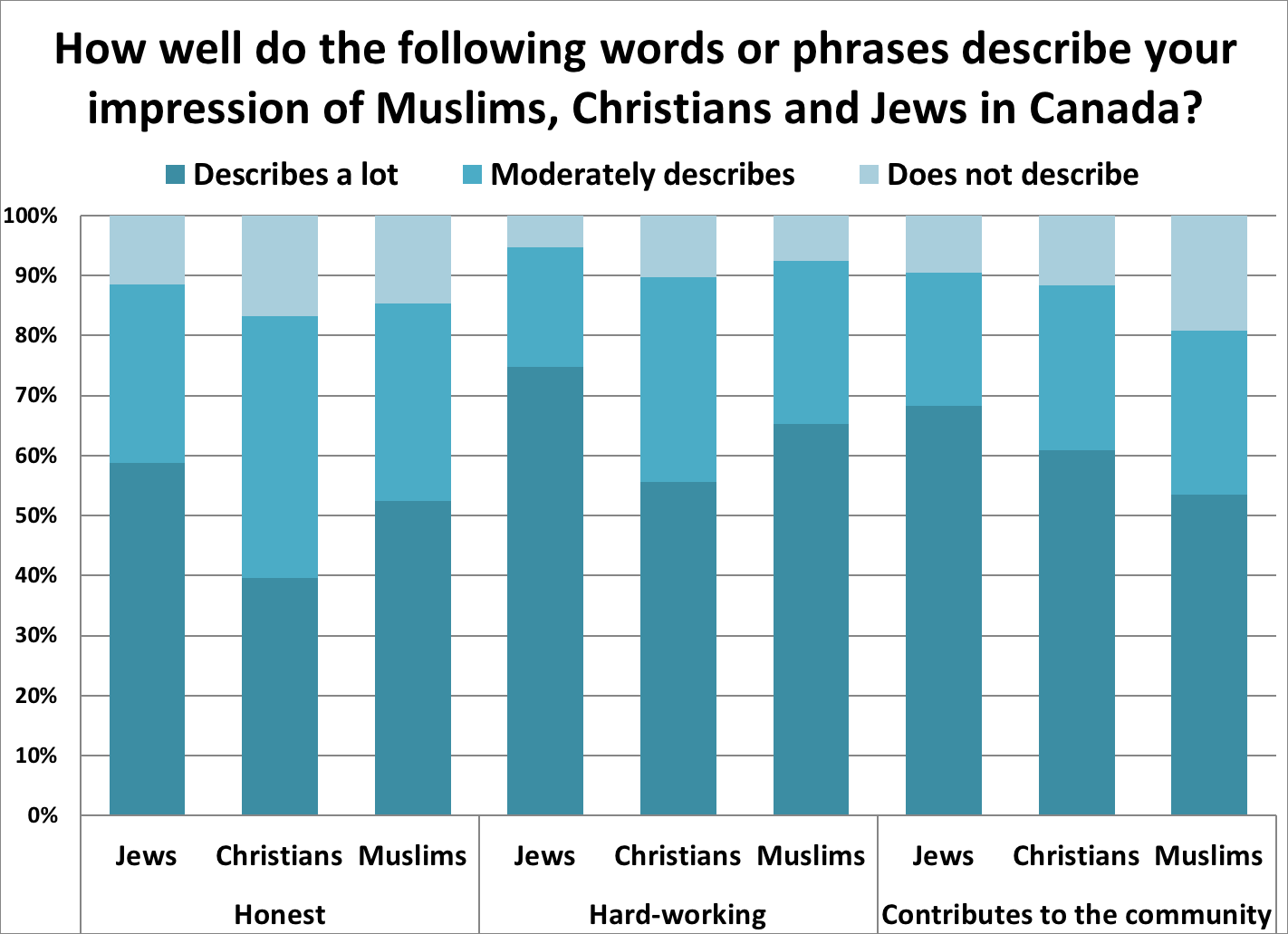

Chart 8: How much do honest/hard-working/’contributes to the community’ describe your impression of Muslims/Christians/Jews in Canada?

Chart 9: How much do ‘set in their ways’/’keeps to themselves’/’oppressive of women’ describe your impression of Muslims/Christians/Jews in Canada?

Chart 10: How much do fanatic/violent/’poorly educated’ describe your impression of Muslims/Christians/Jews in Canada?

Survey respondents were asked their opinion on 12 different words/phrases, so this question generated large amounts of data, and there are many possible observations of interest.

First, the data makes clear that many Canadians hold negative stereotypes about Muslims. For example, as compared to Christians and Jews, survey respondents viewed Muslims as relatively less tolerant, less adaptable, and less open-minded. The worst comparative rankings of Muslims are found with the categories “violent,” and “oppressive of women.” Notably, 14% of Canadians significantly described Muslims as “violent,” vs. only 3% for Christians, and 2% for Jews. Worse, 45% of Canadians viewed Muslims as “oppressive of women,” vs. 13% for Christians, and 12% for Jews. Overall, Muslims were rated worst in all but two of the twelve categories – “honest” and “hard working” – where they enjoyed a slightly more favourable rating than Christians.

Respondents who identified as Conservative and BQ supporters had the least positive impression of Muslims. This may explain why Conservative and Quebec politicians tend to engage in the most polarizing rhetoric vis-à-vis Islamophobia. For example, on multiple occasions, former PM Stephen Harper himself declared that the niqab (a veil that some Muslim women wear over their face) “is rooted in a culture that is anti-women.”[34]

Compared to Christians and Muslims, Jews were almost always the most positively viewed religious group by survey respondents. This finding confirms CIJA’s recent data measuring Canadian attitudes toward Jews. In November 2017, CIJA stated, “Public opinion studies consistently show that many Canadians hold a favourable view of Jews and that Jews enjoy higher favourability ratings than adherents of almost every other religion.”[35]

5. Canadians are far less comfortable with a family member becoming engaged to a Muslim vs. someone of another religious faith

This question was a split sample, whereby half of the respondents were randomly asked one of two related questions:

- “Using a scale of 1 to 5, how comfortable would you feel if a member of your family became engaged to someone of a different religious faith?”

- “Using a scale of 1 to 5, how comfortable would you feel if a member of your family became engaged to a Muslim?”

Chart 11: How comfortable would you feel if a member of your family became engaged to someone of a different religious faith/a Muslim?

Most religious traditions teach adherents not to marry “outside the faith.” As such, one’s reaction to a family member getting engaged to be married to someone of a different religious faith can be very visceral. As such, this question sought to go beyond philosophical introspection and instead challenge respondents with a scenario which would elicit an instinctive and personal reaction: the welcoming of a Muslim into one’s family.

Not surprisingly, all categories of respondents had individuals who were uncomfortable with family members getting engaged to someone of a different religious faith. Overall, 12 percent of Canadians were uncomfortable with a family member getting engaged to someone of a different religious faith. Yet this figure rocketed to 31 percent when respondents considered a family member getting engaged to a Muslim. Challenged in this very personal way, Canadians are far more biased against Muslims than against people of other religious faiths.

As the chart above demonstrates, across all political parties, Canadians are less comfortable with a family member becoming engaged to a Muslim, vs. a different religious faith. By far, the respondents who expressed the strongest discomfort with the notion of a family member being engaged to a Muslim were those who identified as Conservative supporters (50%) and Bloc Quebecois supporters (49%). Nevertheless, even 18 percent of NDP supporters, whose leader was elected on slogans of “love and courage,”[36] were uncomfortable with the thought of having a family member getting engaged to a Muslim.

As with much of the data from this survey, age was an especially important – and encouraging – indicator of Canadian attitudes. Young Canadians (e.g. 35 and younger) were half as likely to be uncomfortable with a family member getting engaged to a Muslim than the average.

6. Canadians believe in the protection of religious rights generally, but are less concerned for the religious rights of Muslims

This question took a split sample approach where respondents were randomly asked one of two related questions:

- How important do you believe it is that the government protect the rights of all Canadians to practice their religion?

- How important do you believe it is that the government protect the rights of Muslims to practice their religion?

Chart 12: How important do you believe it is that the government protect the rights of all Canadians/Muslim Canadians to practice their religion?

Freedom to practice one’s religion is a right which is cherished in all of the world’s liberal Western democracies. Thus, it was not surprising that the survey results indicate that 82 percent of respondents gave importance to religious freedom. Nevertheless, only 68 of Canadians give importance to the protection of the right of Muslims to practice their religion. Thus, while Canadians believe it is important to protect religious freedoms generally, they are less concerned about protecting the religious freedoms of Muslims in Canada.

As with many of the questions in this survey, Canadians’ political affiliations had a strong bearing on their attitudes on religious freedom. Respondents who identified as Liberals, NDP or Green were the most consistent in their attitudes on the protection of religious freedom for all – although there were some interesting differences. Conservative supporters, however, exhibited the most glaring double standard on this question: whereas 80 percent of Conservatives gave importance to the protection of religious freedom overall, only 49 percent gave importance to the protection of religious freedom for Muslims.

Two other demographics which exhibited a double standard on this question were respondents who identified as Christian (87% vs. 65%), and those who identified as French ancestry (73% vs. 57%). Quebecers also stood out as a group. They gave relatively less importance to protecting religious freedom overall (only 65%), and even less importance to protecting the religious practices of Muslims (only 54%.)

7. Only half of Canadians recognize the diversity of views among Muslim Canadians

The following question was put to respondents:

“Using a scale of 1 to 5, how varied do you believe the views of Canadian Muslims are? Please use a scale where 1 means you believe Canadian Muslims are quite uniform in their views and 5 means you believe Canadians Muslims are very diverse in their views.”

Chart 13: How varied do you believe the views of Canadian Muslims are?

Within every religion, there is a diversity of views, values, and practices. This question was included in the survey to determine to what degree Canadians are aware of the diversity found within the Muslim community. Of course, the more monolithic one’s view of a particular group, the easier it is to attribute broad stereotypes.[37] The results of this survey question suggest that a large number of Canadians don’t realize the diversity that exists within the Muslim community. In fact, a full 17 percent of all Canadians consider the Muslim community to be largely uniform in its views.

Canada’s Muslims come from various regions and backgrounds. Just like Christianity, there are dozens of different theological traditions in Islam, and all these traditions are represented within in Canada’s Muslim community: e.g. Sunni, Shia, Ismaili, Sufi, etc. Canada’s Muslims also have widely differing religious dress based on their religious interpretations, and their ethnic or national origins. For example, a Pakistani woman will wear a hijab in a much different style than an Indonesian or a Lebanese Muslim. Some Muslim countries impose the hijab, while others ban it. Other Muslim dress, for both men and women, also differs from country to country, and Canada’s Muslim community reflects all of these differences.

Comparing the response to this question with the response to other questions in this survey, there is a clear correlation between those segments of the population who view the Muslim community as highly uniform, and those who have Islamophobic views. For example, 27% of survey respondents who self-identify as Conservative supporters felt the Muslim community had uniform views. This same demographic was by far the least comfortable with having a family member get engaged to a Muslim. Similar observations are possible when considering respondents from Quebec, or Bloc Quebecois supporters.

Education also played a role in respondents’ understanding of the heterogeneity of Muslim views. Between those with a high school education and those with postgraduate degrees, there is more than a twenty percent difference in the recognition of the diversity of Muslim views. A post-secondary education was also a statistically significant indicator favouring respondents’ comfort level in having a family member get engaged to a Muslim. These statistics show a correlation between education and Canadian levels of Islamophobia.

While it is not depicted in the chart, it is also important to note that over a quarter of respondents felt that Muslims are “neither” uniform nor diverse in their views. In addition, 10% of respondents chose the “Don’t Know/No Response” (DK/NR) category. As such, many respondents were either unable to formulate a confident opinion, or unable to answer the question. We speculate that this phenomenon is due to a genuine lack of familiarity with Muslim views, which likely stems from a lack of direct personal interaction with Canada’s Muslim community.

8. Canadians understand what Islamophobia is; they consider that Islamophobia is a problem; and they expect the government to do something about it

The following charts represent the results from the final question in our survey whereby respondents were given multiple statements and asked to express whether they agreed or disagreed with them. Each of the statements presented in the question mirrored public statements made recently by Canadian political leaders:

The following are comments about Islamophobia that have been made publicly in Canada recently. To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements?

- The definition of Islamophobia is not clear to me

- Islamophobia does not exist in Canada

- Islamophobia is an increasingly disturbing problem in Canada

- The government must take action to combat Islamophobia in Canada

- The concept of Islamophobia is having the effect of limiting free speech in Canada

Chart 14: To what degree to you agree with the following statements about Islamophobia?

Chart 15: By political affiliation: The definition of Islamophobia is not clear to me

Chart 16: By political affiliation: Islamophobia is an increasingly disturbing problem in Canada

Chart 17: By political affiliation: The government must take action to combat Islamophobia in Canada

The responses gathered from this question indicate that the majority of Canadians understand the definition of Islamophobia, they consider Islamophobia to be a problem, and they believe the Canadian government must take steps toward combatting Islamophobia in Canada. However, as made evident in the graphs above, the responses to each of the statements in this question were extremely politically polarized. Again and again, with each statement, the views of Liberal, NDP and Conservative supporters differed in statistically significant ways: the Liberals and NDP on one side, and the Conservatives on the other.

Response to the statement, “The definition of Islamophobia is not clear to me.”

Survey respondents were asked if they agreed with the statement, “The definition of Islamophobia is not clear to me.” Many Canadian Conservative politicians have questioned the validity of the term “Islamophobia,” and have gone so far as to claim that most Canadians are uncomfortable with the term “Islamophobia” because they do not understand what it means.[38] The results of this survey tell a very different story:

- Overall, 70% of Canadians disagreed that the definition of Islamophobia is not clear to them, showing that Canadians understand what Islamophobia is, while

- 59% of Conservative supporters confirm that they too understand what Islamophobia is.

While a strong majority of Canadians understand what Islamophobia is, a quarter of Canadians nevertheless still seem confused by term. Age and education both played a factor in the response to this question: those respondents who are under 35 (81%), and those with higher education such as a bachelor’s degree (77%) are more likely to have a clear understanding of Islamophobia. As such, there is still work to be done to educate Canadian society about discrimination against Muslims.

Response to the statement, “Islamophobia does not exist in Canada.”

81% of respondents overall disagreed with the statement, “Islamophobia does not exist in Canada.” This result confirms the findings of a December 2016 Abacus poll where 79% of Canadians agreed there is “some” or “a lot” of discrimination against Muslims in Canada.[39]

Response to the statement, “Islamophobia is an increasingly disturbing problem in Canada.”

While an Angus Reid poll of March 2017 showed that Canadians were split between believing Islamophobia is a serious problem (45%) and believing that Islamophobia had been “overblown by politicians and the media” (55%)[40], a majority of our respondents (57%) agreed with the statement, “Islamophobia is an increasingly disturbing problem in Canada.” As stated above and depicted in the graphic, the response to this statement and other statements was highly politically polarized: only Conservative supporters were in majority opposition to this statement.

Response to the statement, “The government must take action to combat Islamophobia in Canada”

A March 2017 Angus Reid poll indicated that only 38% of Canadian Liberal supporters would have voted in support of motion M-103[41], a government motion to combat religious discrimination (including Islamophobia) in Canada. Nevertheless, our survey results demonstrate that 70% of Canadians (and 77% of Liberal supporters) believe the government must take action to combat Islamophobia in Canada. Only survey respondents who identified as Conservative or BQ supporters had a majority expressing disagreement with this statement. Again, as depicted in the graphic, survey results were highly politically polarized.

Response to the statement, “The concept of Islamophobia is having the effect of limiting free speech in Canada”

Some politicians and pundits suggested that the passage of Parliament’s motion M-103 (March, 2017) could lead to a government crackdown on speech critical of Islam in Canada.[42] Canadian law protects freedom of speech except when the speech is deemed “hate speech” – a designation which requires incitement to violence and/or public disorder. So reasonably speaking, such fears are highly farfetched.

Nevertheless, since almost half (49%) of all survey respondents agreed with the statement, “The concept of Islamophobia is having the effect of limiting free speech in Canada,” it is clear that many Canadians have been spooked by fear-mongering around free speech. While Liberal and NDP supporters differed from Conservative supporters, both in a statistically significant way, even important numbers of Liberal supporters (43%) and NDP supporters (37%) agreed with this statement.

All Canadians were horrified by the images of ISIS militants committing atrocities and the acts of terrorism committed by Islamic fundamentalists in recent years. Harsh criticism of such acts, and the circumstances which lead to the radicalization of individuals will always be protected in Canada. Nevertheless, this survey result makes clear that there is concern across the political spectrum around the freedom to criticize radical religious practices.

APPENDIX 1: Other recent surveys on Religious Discrimination and Islamophobia in Canada

What do Canadians say about Muslims and Islam?

A March 2016 Leger survey[xliii] found that only 43% of Canadians hold positive opinions of Muslims, a decline of 3% since 2012. Net positive opinion of Muslims was 49% amongst English respondents, but only 24% amongst French respondents.

“I was most surprised by the extent to which there was a decline in comparison to previous polling we’ve done in attitudes towards Muslims…I fully expected to see a decline but the decline was a lot steeper than I anticipated, particularly, in the Province of Quebec.”

- Jack Jedwab, president of the Association for Canadian Studies[xliv]

A July 2016 poll by MARU/VCR&C[xlv] measuring public perceptions of ethnicity and immigration in Ontario found that “only a third of Ontarians have a positive impression of the religion [Islam] and more than half feel its mainstream doctrines promote violence (an anomaly compared to other religions).” Comparing Canada’s six major mainstream religions, Islam is the most likely to be viewed by the respondents as a promoter of violence, followed by Sikhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Judaism and Buddhism. Three-quarters of Ontarians said they felt Muslim immigrants have fundamentally different values, largely due to perceived gender inequality.

“Only a third of Ontarians have a positive impression of the religion and more than half feel its mainstream doctrines promote violence (an anomaly compared to other religions).”

- Ontario Council of Agencies Serving Immigrants[xlvi]

A December 2016 Forum poll[xlvii] found that Muslims were the target of the most racial bias in Canada. Four-in-ten (41%) of Canadians expressed some level of bias, or unfavourable feelings, against identifiable racial groups, and the one group most likely to be a target was Muslims (28% unfavourable feelings, 54% favourable feelings). After Muslims, the group most likely to suffer bias was First Nations people (16% unfavourable feelings, 71% favourable). Muslims excited the most animosity in Quebec (48% unfavourable) and among Conservatives (40% unfavourable).

In a December 2016 Abacus poll,[xlviii] 79% of Canadians said that there is “some” or “a lot” of discrimination towards Muslims in Canada, and 67% said the same thing about discrimination towards Indigenous people. Almost one-in-two said there is a lot of discrimination against people of the Muslim faith, far more than towards any of the other groups tested. The view that there is significant discrimination against Muslims crossed all demographic groups and regions, although Quebecers were least likely to say it is widespread, compared to other regions. In Canada, women and young people were generally more likely than others to see discrimination, while men and older people were least likely to see it.

“Canadians see their country as a tolerant place, but far from perfect. Tensions have been rising in the US and other parts of the world towards people of the Muslim faith and we acknowledge that those same influences are pretty widespread here in Canada.”

- Bruce Anderson, Chairman, Abacus Data[xlix]

In a March 2017 Angus Reid poll,[l] 42% of Canadians said they would vote against the House of Commons motion M-103, condemning “Islamophobia and all forms of systemic racism and religious discrimination,” while fewer than three-in-ten would vote for it.

Some 68% of those who voted for the Conservatives in 2015 said they would vote against M-103. Only 38% of Liberal supporters said they would vote in favour of the motion, while fully 33% would vote against.

While relatively few Canadians outside of Quebec said they knew a lot of people who are distrustful of Canadian Muslims, most respondents agreed that “Canadian Muslims face a lot of discrimination in their daily lives.” Some 61% felt this way, including higher numbers of women and younger respondents (68% of each group).

A March 2017 CROP poll[li] found that 74% of respondents said they would either be “very” or “somewhat” in favour of screening immigrants with a test on Canadian values. One-in-four Canadians, and 32% of Quebecers, were “strongly” or “somewhat” in favour of a Donald Trump-style ban on Muslims immigrating to Canada.

In Quebec, while 65% of people would be OK with a new Catholic church in their neighbourhood, only 40% felt the same way about a mosque. In the rest of Canada, 76% would be OK with a Catholic church, while 56% would be OK with a mosque.

In Quebec, 62% perceived the hijab to be a sign of submission, while in the rest of Canada 48% felt the same. Fifty-seven percent of Quebecers felt as if Muslims are “poorly” or “somewhat poorly” integrated into society, versus 47% of respondents in the rest of Canada.

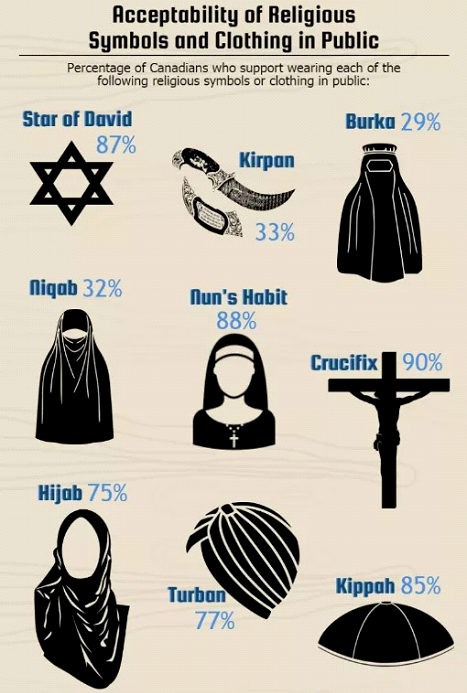

Acceptability of religious symbols and clothing in public

An April 2017 Angus Reid poll[lii] found that Islam is viewed unfavourably by almost half of Canadians (46%). A similarly negative sentiment was found when discussing religious clothing associated with that faith – the burka and niqab. Only one-in-three Canadians support a person wearing the niqab (32%) or the burka (29%), while a strong majority support wearing the nun’s habit (88%), kippah (85%), turban (77%) or hijab (75%).

How would Canadians feel if one of their children were to marry a partner from another faith? Very few said they would not be accepting of their child marrying a Christian, but that number rose to one-in-five for a Sikh (21%) and one-in-three for a Muslim (32%).

According to a June 2017 Abacus poll[liii] conducted for Macleans magazine, only 60% of Canadians think Islamophobia is a problem in Canada, and 38% somewhat or strongly disagree that it’s an issue at all. Denying its existence suggests that Canadians remain isolated from their Muslim neighbours, leading them to treat them as an alien group.

“I think that despite a lot of progress, post 9/11, many Canadians still view Muslims as a homogenous group with only one foot inside the Canadian cultural identity; and any time you can define so many people as the ‘other,’ you can start to strip away the complexity of a community, which allows you to scapegoat and vilify.”

- Actor, filmmaker and lawyer Arsalan Shirazi[liv]

A September 2017 Angus Reid poll[lv] of Quebecers’ opinions regarding Quebec’s Bill 62, prohibiting face-coverings such as niqabs and burkas for people administering or receiving public sector services, found that 91% of francophones and 67% of anglophones support the legislation. Younger Quebecers (those ages 18 – 34) were more tepid in their support for the legislation, though they still support it by a three-to-one margin (74% to 26%) overall.

An October 2017 Angus Reid poll[lvi] found that 40% of residents of Canada’s other nine provinces said women should be prohibited from visiting government offices while wearing a niqab. A further 31% said such behaviour should be “discouraged but tolerated,” while only 28% said it should be “welcome.”

Nearly two-thirds (64%) of those who supported the Conservatives in 2015 would prohibit women from receiving government services while wearing a niqab, compared to 39% of Liberal supporters and 44% of NDP supporters who said the same.

In a November 2017 Angus Reid poll[lvii] on faith and religion in public life, 46% of respondents said that Islam was “damaging” Canada and Canadian society, while only 13% said that it was “benefitting”. Twice as many Canadians said the presence of Islam in their country’s public life is damaging as said the same about any other religion. Furthermore, two-thirds (65%) of those asked about Islam say the religion’s influence in Canadian public life is growing.

These two findings – that almost half of Canadians view the presence of Islam as a bad thing for their country and that two-thirds see Islam’s influence in society as growing – suggest an outsized focus on a group that, while growing rapidly, makes up less than four per cent of Canada’s total population.

“Twice as many Canadians say the presence of Islam in their country’s public life is damaging as say the same about any other religion, a finding that follows a well-documented pattern in Angus Reid Institute polling in recent years. Namely: if Islam is involved, a significant segment of Canadians will react negatively.”

– Angus Reid Institute, November 2017[lviii]

What do Canadian Muslims say about life in Canada?

According to a January 2016 Environics poll[lix] of 600 Canadian Muslims, an overwhelming majority have a strong attachment to their country and feel that Canada is heading in the right direction. Eight-in-ten (83%) Muslims reported being “very proud” to be Canadian, an increase of 10 points since 2006. This was in contrast to non-Muslim Canadians — only 73% of whom said they were “very proud” to be Canadian.

A majority of Muslim Canadians agreed that most Muslims coming to Canada want to adopt Canadian customs and ways of life, while just 17% thought they want to remain distinct.

Thirty percent of Muslim Canadians said they have experienced discrimination because of their religion, ethnicity or culture over the past five years — significantly higher than the reported experience of discrimination among the general population. Fully 62% Muslims reported being very or somewhat worried about discrimination, increasing to 72% among young Muslims and 83% among Canadian-born Muslims.

Two-thirds of respondents were worried about how the media portrays Muslims in Canada.

A May 2016 Think for Actions survey[lx] of Alberta Muslims found that 98% of the participants considered themselves to be proud of being Muslim Canadian citizens. Eighty-four percent showed a willingness to adapt to Canadian values while still maintaining their Muslim identity, and 88% were actively involved in activities for non-Muslim organizations.

Despite being active members of society, half of the Muslim participants reported being victims of abuse, especially verbal abuse. Media was seen as one of the contributing factors to this, 83% of the participants agreed that television news reports portrayed Muslim Canadians in a negative light.

Another Think for Actions survey,[lxi] released in September 2017,[lxii] found that 78% of Canadians agreed that Muslims should adopt Canadian customs and values but maintain their religious and cultural practices. Some 88% of those surveyed said Muslims should be treated no differently than any other Canadian, but 72% also believed there has been an increasing climate of hatred and fear towards Muslims in Canada and that it will get worse.

APPENDIX 2: Text of Motion M-103

42nd Parliament, 1st Session

M-103 – Systemic racism and religious discrimination

Text of the Motion

That, in the opinion of the House, the government should: (a) recognize the need to quell the increasing public climate of hate and fear; (b) condemn Islamophobia and all forms of systemic racism and religious discrimination and take note of House of Commons’ petition e-411 and the issues raised by it; and (c) request that the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage undertake a study on how the government could (i) develop a whole-of-government approach to reducing or eliminating systemic racism and religious discrimination including Islamophobia, in Canada, while ensuring a community-centered focus with a holistic response through evidence-based policy-making, (ii) collect data to contextualize hate crime reports and to conduct needs assessments for impacted communities, and that the Committee should present its findings and recommendations to the House no later than 240 calendar days from the adoption of this motion, provided that in its report, the Committee should make recommendations that the government may use to better reflect the enshrined rights and freedoms in the Constitution Acts, including the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[lxiii]

[1] “Defining ‘Islamophobia.’” University of California, Berkely Center for Race and Gender. Accessed 7 April 2014.

[2] Abu Sway, Mustafa, “Islamophobia: Meaning, Manifestations, Causes,” Palestine-Israel Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2&3, 2005

[3] Goodfield, Kayla, “‘I’m not racist’: Jagmeet Singh’s heckler posts video defending herself,” CTV News Toronto, Sept. 11, 2017 https://toronto.ctvnews.ca/i-m-not-racist-jagmeet-singh-s-heckler-posts-video-defending-herself-1.3584886

[4] Semati, Mehdi. “Islamophobia, Culture and Race in the Age of Empire.” Cultural Studies 24, no. 2, 2010. p. 256-275.

[5] “Observations sur l’apperçu provisoire des grandes lignes du rapport déposé par le Canada auprès du Comité pour l’élimination de la discrimination raciale.” CJPME Foundation. March 2015, p. 2.

[6] Geddes, John. “Canada anti-Muslim sentiment is rising, disturbing new poll reveals.” Macleans. 3 October 2013.

[7] Ibid, CJPME Foundation.

[8] “Canadian Muslims face high unemployment.” Iqra. March 31, 2015. http://iqra.ca/2015/canadian-muslims-face-high-unemployment/.

[9] Eid, Paul et al. “Mesurer la discrimination à l’embauche subie par les minorités racisées: résultats d’un ‘testing’ mené dans le grand Montréal.” Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse. May 2012.

[10] Gordon, Sean. “Quebec town spawns uneasy debate.” The Toronto Star. 5 February 2007.

[11] Jamil, Uzma. “Discrimination experienced by Muslims in Ontario.” Ontario Human Rights Commission. January 2012.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Jahangir, Junaid. “Muslims Stand Against ISIS, Too.” The Huffington Post. 27 August 2014.

[14] “E-411 (Islam).” Parliament of Canada. June 8, 2016. https://petitions.ourcommons.ca/en/Petition/Details?Petition=e-411.

[15] Thomas Woodley. “In Case You Missed it, Canada Passed an Anti-Islamophobia Motion.” Huffington Post. November 2, 2016. http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/thomas-woodley/canada-anti-islamophobia-.law_b_12753924.html.

[16] “New Democrats Secure Victory Fighting Islamophobia.” NDP. October 26, 2016. https://www.facebook.com/FMCCMF/videos/1091356544312435/.

[17] “CJPME Saddened and Disgusted by Attack on Quebec City Mosque.” CJPME. January 30, 2017. http://www.cjpme.org/pr_2017_01_30.

[18] “Systemic Racism and Religious Discrimination.” Legislative Debate (Hansard). 42nd Parl., Ist Sess. February 15, 2017. Online. http://www.ourcommons.ca/Parliamentarians/en/members/Iqra-Khalid(88849)/Motions?documentId=8661986%2520.

[19] “Systemic Racism and Religious Discrimination.” Legislative Debate (Hansard). 42nd Parl., Ist Sess. February 15, 2017. Online. http://www.ourcommons.ca/Parliamentarians/en/members/Iqra-Khalid(88849)/Motions?documentId=8661986%2520

[21] Alex Boutilier. “Liberal MP swamped by hate mail, threats over anti-Islamophobia motion in Commons.” The Hamilton Spectator. February 17, 2017. https://www.thespec.com/news-story/7145978-liberal-mp-swamped-by-hate-mail-threats-over-anti-islamophobia-motion-in-commons/.

[22] Ryan Maloney. “M-103: Liberal Government Will Support Iqra Khalid’s Motion Condemning Islamophobia.” The Huffington Post. February 15, 2017. http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2017/02/15/motion-103-iqra-khalid-melanie-joly-liberals-tories_n_14776116.html.

[23] Individuals making this argument might likewise dilute the statement “Black lives matter” by saying, “All lives matter.” While it is true that all lives matter, white lives in Canada have always “mattered,” while black lives have not been valued in the same way. “Black lives matter” puts the emphasis on the fact that society overall has historically attributed less value to black lives based on several independent empirical measures, e.g. deaths in police custody, incarceration rates, graduation rates, life expectancy, etc. In the same way, while religious discrimination is never acceptable, in 2017, it is Muslims in Canada who foremost face religious discrimination.

[24] Iqra Khalid. “M-103: Systemic Racism and Religious Discrimination.” Parliament of Canada. http://www.ourcommons.ca/Parliamentarians/en/members/Iqra-Khalid(88849)/Motions?documentId=8661986%2520.

[25] In the discussion of the survey results, we frequently refer to survey “respondents,” although it would be more statistically appropriate to use the term “Canadians,” as the survey results were weighted. That is, the results reflect the Canadian population, rather than the actual pool of people who did the survey.

[26] Justin Trudeau. “Diversity is Canada’s Strength.” Justin Trudeau - PMO. November 26, 2015. https://pm.gc.ca/eng/news/2015/11/26/diversity-canadas-strength.

[27] “Judge rules Quebec woman should not have been barred from court for wearing hijab.” CTV News/The Canadian Press. October 6, 2016. https://montreal.ctvnews.ca/judge-rules-quebec-woman-should-not-have-been-barred-from-court-for-wearing-hijab-1.3104624.

[28] Khandaker, Tamara, “Quebec just banned face veils for people receiving government services.” Vice News. October 18, 2017. https://news.vice.com/en_ca/article/3kp549/face-veils-are-now-banned-for-quebecers-receiving-government-services.

[29] “Stephen Harper playing very divisive game with Niqabs.” CBC. September 21, 2015. http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/canada-election-2015-niqab-bloc-1.3236837.

[30] Marilla Steuter-Martin. “Breaking down Bill 62.” CBC. October 25, 2017. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/bill-62-examples-ministry-release-1.4369347.

[31] “Stephen Harper doubles down on niqab debate.” National Post. March 11, 2015. http://nationalpost.com/news/politics/stephen-harper-doubles-down-on-niqab-debate-rooted-in-a-culture-that-is-anti-women.

[32] “Police-reported hate crime 2016.” Statistics Canada. November 28, 2017. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/171128/dq171128d-eng.htm.

[33] Tamara Khandaker. “Hate crimes increased in Canada last year.” Vice News. November 28, 2017. https://news.vice.com/en_ca/article/4344vp/hate-crimes-increased-in-canada-last-year.

[34] Stephen Chase. “Niqabs rooted in a culture that is anti-women: Harper says.” The Globe and Mail. March 10, 2015. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/niqabs-rooted-in-a-culture-that-is-anti-women-harper-says/article23395242/.

[35] “One in five Canadians see Judaism benefiting Canada: Study.” The Canadian Jewish News. November 24, 2017. http://www.cjnews.com/news/canada/one-five-canadians-see-judaism-benefiting-canada-study.

[36] “With Love and Courage,” Jagmeet Singh NDP. 2017.

[37] “Islamophobia: A Challenge for us all.” The Runnymede Trust. https://www.runnymedetrust.org/uploads/publications/pdfs/islamophobia.pdf; Shanifa Nasser. “How Islamophobia is driving young Muslims to reclaim their identity.” CBC. April 28th, 2016. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/environics-muslim-canadian-survey-1.3551465.

[38] David Anderson, “Systemic Racism and Religious Discrimination.” Legislative Debate (Hansard). 42nd Parl., 1st Sess. February 15th, 2017. Online. http://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/house/sitting-141/hansard

[39] “Muslims and Indigenous People Face the Most Discrimination in Canada, According to Canadians.” Abacus Data. December 29, 2016. http://abacusdata.ca/muslims-and-indigenous-people-face-the-most-discrimination-in-canada-according-to-canadians/.

[40] “M-103: If Canadians, not MPs, voted in the House, the motion condemning Islamophobia would be defeated.” Angus Reid Institute. March 23, 2017. http://angusreid.org/islamophobia-motion-103/.

[41] See Appendix 2 for a full text of the motion.

[42] Lawton, Andrew, “COMMENTARY: Free speech can’t be a casualty of Canada’s ‘whole-of-government’ approach to Islamophobia,” Global News. September 22, 2017. https://globalnews.ca/news/3761603/commentary-free-speech-cant-be-a-casualty-of-canadas-whole-of-government-approach-to-islamophobia/.

[xliii] “State of Relations 2016,” Canadian Race Relations Foundation, undated, but based on a survey conducted in March, 2016, https://www.crrf-fcrr.ca/en/programs-3/capturing-the-pulse-of-the-nation-2/item/26625-state-of-relations-2016

[xliv] Sevunts, Levon, “Majority of Canadians have negative views of Muslims: survey,” Radio Canada International, March 21, 2016, https://www.crrf-fcrr.ca/en/programs-3/capturing-the-pulse-of-the-nation-2/item/26625-state-of-relations-2016

[xlv] “Survey Summary,” Ontario Council of Agencies Serving Immigrants, July 5, 2016, http://www.torontoforall.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/OCASI_Survey_Summary_July-5_2016.pdf

[xlvi] Ibid.

[xlvii] “Muslims the Target of Most Racial Bias,” The Forum Poll, December 19, 2016, http://poll.forumresearch.com/post/2646/muslims-the-target-of-most-racial-bias/

[xlviii] Anderson, Bruce, and Coletto, David, “Muslims and Indigenous People Face the Most Discrimination in Canada, According to Canadians,” Abacas Data, December 29, 2016, http://abacusdata.ca/muslims-and-indigenous-people-face-the-most-discrimination-in-canada-according-to-canadians/

[xlix] Ibid.

[l] “M-103: If Canadians, not MPs, voted in the House, the motion condemning Islamophobia would be defeated,” Angus Reid Institute, March 23, 2017, http://angusreid.org/islamophobia-motion-103/

[li] “Les Canadiens, le populisme, la xénophobie,” Radio Canada, rapport présenté par CROP, February, 2017, http://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelles/special/2017/03/sondage-crop/Sondage%20CROP-Radio-Canada.pdf

[lii] “Religious Trends: Led by Quebec, number of Canadians holding favourable views of various religions increases,” Angus Reid Institute, April 4, 2017, http://angusreid.org/religious-trends-2017/

[liii] Williams, Malayna, “Too many Canadians don’t recognize the Islamophobia in their country,” Maclean’s, June 11, 2017, http://www.macleans.ca/society/too-many-canadians-dont-recognize-the-islamophobia-in-their-country/

[liv] Ibid.

[lv] “Quebec Politics: Major support for Bill 62, far less approval for government’s handling of border issues,” Angus Reid Institute, October 4, 2017, http://angusreid.org/quebec-provincial-issues-sept/

[lvi] “Four-in-ten outside Quebec would prohibit women wearing niqabs from receiving government services,” Angus Reid Institute, October 27, 2017, http://angusreid.org/bill-62-face-covering/

[lvii] “Faith and Religion in Public Life: Canadians deeply divided over the role of faith in the public square,” Angus Reid Institute, November 16, 2017, http://angusreid.org/faith-public-square/

[lviii] Ibid.

[lix] “Survey of Muslims in Canada 2016,” Environics Institute, April 30, 2016, https://www.environicsinstitute.org/projects/project-details/survey-of-muslims-in-canada-2016

[lx] Ali Zaidi, Mukarram et al, “Muslim Community Engagement Study: Highlights of the Results of the RISC Survey,” The Western Minaret, Muqarnas Press, May, 2016, http://thewesternminaret.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/RISC-study-format-1.pdf

[lxi] “Press Release: Release of Canadian Community Engagement Study,” Think for Actions, March 13, 2017, http://www.thinkforactions.com/site/risc2016/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Press%20Release-%20Canadian%20Community%20Engagement%20Study.pdf